Published: Monday, February 04, 2008

|

|

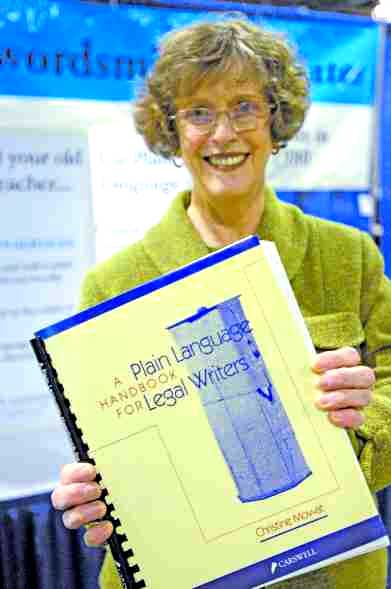

Christine Mowat Photograph by : Troy Fleece, Leader-Post |

Be concise. Watch your punctuation. Write for your readers.

The tenets are simple, but the potential impact of the plain language movement is broad.

"Language is the property of the people," says Christine Mowat, president of Wordsmith Associates, an Edmonton-based firm that teaches clear communication to governments and organizations around the country.

On Sunday, Mowat shared her skills with delegates of the Saskatchewan Urban Municipalities Association (SUMA) convention in Regina, hoping to demonstrate how plain language can help municipalities operate more effectively, save money, and better serve the public.

Mowat says municipal writing is often comprised of extremely long sentences and overly formalized language, peppered with institutional catch phrases and "bureaucratese." Not only is this kind of writing cumbersome to read, Mowat says it's difficult for many members of the public to comprehend.

"There is no match between literacy levels and the way documents are written," she says, noting people regularly sign important governmental, financial or legal documents they don't understand.

That's where plain language comes in.

Mowat uses a model which stresses lean language, an active voice, good organization, and proper English to make writing clearer and simpler -- all while maintaining the meaning of the original document. To illustrate her point, Mowat pared down the City of Saskatoon's vision statement from a lengthy 48-word sentence to three shorter, clearer sentences expressing the same ideas. (Reader studies have shown that sentences should have 15 to 25 words, and 35 words at the most, Mowat notes.)

Mowat recently wrote a 120-page bylaw for the City of Toronto in plain language, after Toronto's city council began moving to plain language last year.

But Mowat is quick to point out that plain language doesn't always mean shorter and simpler. Sometimes longer words are easier to understand than shorter ones, she says, and technical jargon can still be appropriate, depending on the context and the common experience of the intended audience. The challenge is to improve the language without changing the message or the legal significance.

"We never dumb it down," she says.

Mowat says plain language not only creates a positive image for organizations and helps them operate more effectively, it also has the potential to save significant amounts of money.

A study by Alberta Agriculture and Food conservatively estimates that department's savings at $3.4 million a year after its forms were rewritten in plain language. Mowat said plain language means members of the public need less support when accessing information, and are more likely to file documents and forms without errors.

But Mowat says there is an ethical principle too, in that plain language recognizes diversity of education, reading level, and ethnic background. She says government and organizations have a responsibility to make language accessible to the public.

"It's a matter of human rights," she says.

© The Leader-Post (Regina) 2008