Sun Oddly Quiet -- Hints at Next "Little Ice Age"?

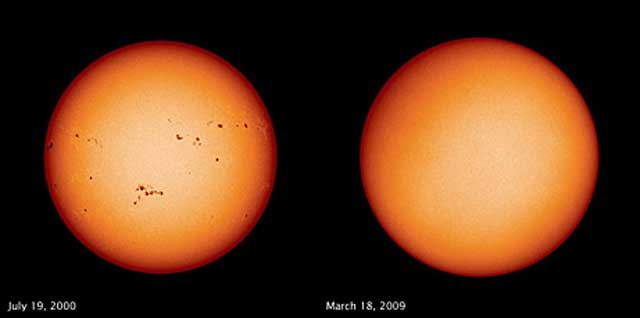

In July 2000 the sun was at a peak in activity, as seen by the speckling of sunspots spied by NASA's Solar and Heliospheric Observatory (SOHO) spacecraft. But the sun was a blank disk in March 2009, when it was the quietest it has been since the 1950s.

The current sunspot deficit has caused some scientists to recall the Little Ice Age of the early 1600s and late 1700s, a prolonged, localized cold spell linked to a decline in solar activity.

Images courtesy SOHO, the EIT Consortium, and the MDI Team

Anne Minard

for National Geographic News

May 4, 2009

A prolonged lull in solar activity has astrophysicists glued to their telescopes waiting to see what the sun will do next—and how Earth's climate might respond.

The sun is the least active it's been in decades and the dimmest in a hundred years. The lull is causing some scientists to recall the Little Ice Age, an unusual cold spell in Europe and North America, which lasted from about 1300 to 1850.

The coldest period of the Little Ice Age, between 1645 and 1715, has been linked to a deep dip in solar storms known as the Maunder Minimum.

During that time, access to Greenland was largely cut off by ice, and canals in Holland routinely froze solid. Glaciers in the Alps engulfed whole villages, and sea ice increased so much that no open water flowed around Iceland in the year 1695.

But researchers are on guard against their concerns about a new cold snap being misinterpreted.

"[Global warming] skeptics tend to leap forward," said Mike Lockwood, a solar terrestrial physicist at the University of Southampton in the U.K. (Get the facts about global warming.)

He and other researchers are therefore engaged in what they call "preemptive denial" of a solar minimum leading to global cooling.

Even if the current solar lull is the beginning of a prolonged quiet, the scientists say, the star's effects on climate will pale in contrast with the influence of human-made greenhouse gases such as carbon dioxide (CO2).

"I think you have to bear in mind that the CO2 is a good 50 to 60 percent higher than normal, whereas the decline in solar output is a few hundredths of one percent down," Lockwood said. "I think that helps keep it in perspective."

(Related: "Don't Blame Sun for Global Warming, Study Says.")

Local Cooling

For hundreds of years scientists have used the number of observable sunspots to trace the sun's roughly 11-year cycles of activity.

Sunspots, which can be visible without a telescope, are dark regions that indicate intense magnetic activity on the sun's surface. Such solar storms send bursts of charged particles hurtling toward Earth that can spark auroras, disrupt satellites, and even knock out electrical grids.

In the current cycle, 2008 was supposed to have been the low point, and this year the sunspot numbers should have begun to climb.

But of the first 90 days of 2009, 78 have been sunspot free. Researchers also say the sun is the dimmest it's been in a hundred years.

The Maunder Minimum corresponded to a profound lull in sunspots—astronomers at the time recorded just 50 in a 30-year period.

If the sun again sinks into a similar depression, at least one preliminary model has suggested that cool spots could crop up in regions of Europe, the United States, and Siberia.

During the previous event, though, many parts of the world were not affected at all, said Jeffrey Hall, an astronomer and associate director at Lowell Observatory in Flagstaff, Arizona.

"Even a grand minimum like that was not having a global effect," he said.

Wild Cards and Uncertainties

Changes in the sun's activity can affect Earth in other ways, too.

For example, ultraviolet (UV) light from the sun is not bottoming out the same way it did during the past few visual minima.

"The visible light doesn't vary that much, but UV varies 20 percent, [and] x-rays can vary by a factor of ten," Hall said. "What we don't understand so well is the impact of that differing spectral irradiance."

Solar UV light, for example, affects mostly the upper layers of Earth's atmosphere, where the effects are not as noticeable to humans. But some researchers suspect those effects could trickle down into the lower layers, where weather happens.

In general, recent research has been building a case that the sun has a slightly bigger influence on Earth's climate than most theories have predicted.

Atmospheric wild cards, such as UV radiation, could be part of the explanation, said the University of Southampton's Lockwood.

In the meantime, he and other experts caution against relying on future solar lulls to help mitigate global warming.

"There are many uncertainties," said Jose Abreu, a doctoral candidate at the Swiss government's research institute Eawag.

"We don't know the sensitivity of the climate to changes in solar intensity. In my opinion, I wouldn't play with things I don't know."