Common practice gives borderline grades a bump

BY JANET FRENCH, THE STARPHOENIX MAY 11, 2009

The passing grade in Saskatchewan high schools is 50 per cent -- except when it's not.

High school students and their families might be surprised to learn that computers at the Ministry of Education take every final grade of 48 and 49 per cent and bump it up to a passing grade of 50.

Furthermore, explains Darryl Hunter, executive director of accountability, assessment and records with the ministry, when a student obtains a grade of between 44 and 49 per cent in a class, and that one mark stands in the way of graduation, the ministry will also nudge it up to 50 per cent.

The point, Hunter says, is to give students who are extremely close to passing the benefit of the doubt.

"It's crystal clear in every student's mind, and every parent's mind, and every educator's mind, and certainly in my mind, that 50 is the (passing grade)," he said. " . . . I don't hear of any people aspiring to a 48."

But speaking on the condition of anonymity, several Saskatoon high school teachers say there's a no-marks land between 45 and 49 per cent, where teachers are discouraged from handing out grades.

"Everybody knows if you want a kid to stay failed you have to give him a 44," says Marvin (not his real name), a Saskatoon high school teacher.

Some high school teachers said they were too afraid for their jobs to discuss the topic, even if their identities were protected.

Marvin said he knows about the provincial policy bumping up grades of 48 and 49, but a leeway of the so-called "six floating marks" on a student's 24th credit were news to him.

He doesn't believe in rounding up arbitrarily -- if his calculations give a student 47 per cent at the end of the term, then that's the mark he submits to the education ministry, he says.

Blurring the line

Likewise, high school teacher Dave (not his real name) says he and his colleagues are told a student's mark must be lower than 45 per cent if they want the student to repeat a class.

"That's a big decision," he says. "It's a kid's year you're dealing with."

The provincial policies on grade-changing were surprising to Dave, who said he'd been told all grades in the 45 to 49 range would be elevated to 50.

"I think it's a little silly," he said. "You've got to have some cut off, and we've decided that it's 48, but we're going to tell people it's 50, so it's not necessarily very honest."

When it's time to submit final grades for the year, high school teacher Peter (not his real name) says his school administrators send out a reminder, telling teachers to "stay away from this area" of grades from 45 to 49.

Not a fan of the province's policies, Peter tries to avoid having his marks bumped up by taking any final grade in the 45 to 49 range and moving it down to a 44 per cent. A fail is a fail whether it's close to the line or not -- that's his philosophy.

"If it's low enough, then the province doesn't touch that mark," Peter says, adding he's "kind of a hard ass" when it comes to grading.

Teachers interviewed say in some cases they and their colleagues feel insulted when the ministry overrides their professional judgment by passing a student the teacher has opted to fail.

"We've worked with that student (for more than) 100 hours over the entire semester," Peter says. "We know what they've achieved and are capable of."

Those failing grades are often determined after second chances to re-take tests, submit late assignments, or do additional work to show they understand the material well enough to pass.

"Kids have never been more supported than they are now," Dave said.

Many chances to pass

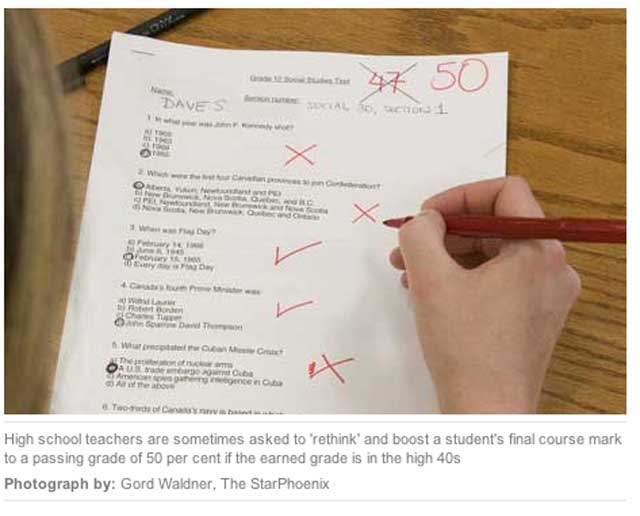

Cindy Coffin, assistant superintendent of learning services for Greater Saskatoon Catholic Schools, says although the school division has no policies about the no-marks land, teachers are sometimes asked to "rethink" any final grades of 47, 48 and 49, and that those numbers are "generally not accepted" as final marks. Practices vary from school to school, with some principals also telling teachers to steer clear of 45s and 46s, she said. "Students need to clearly pass or clearly fail," she said, and a mark of 47 may not be clear.

Saskatoon Public Schools' superintendent of education, John Dewar, says each school reminds teachers of the provincial policies differently -- some orally and others in written memos. After an April interview with The StarPhoenix, Dewar says he contacted division high schools and found some administrators were confused about the policies and may have been sending out the wrong messages.

"I think it's fair to say that we are clearer, and there will be more of that consistent practice . . . to make sure that the only pieces that involve mark adjustment are what the ministry says in its guidelines," Dewar said.

Both divisions are in the process of changing how they grade students, saying they're moving toward giving more qualitative feedback as well as numerical grades. "Sometimes, we've been too quick as educators . . . to put a mark down," Dewar said, calling student assessment an "imperfect" process and a "conundrum."

The art and science of grading

Technically speaking, how do teachers nudge up, or knock down, a grade? Administrators from both divisions say there's several ways, including changing the weighting of tests and assignments, either across the board or negotiated with one student. Re-taking tests and second chances to hand in assignments could also bump a student's grade to passing territory.

But some teachers who do adjust their grades say there's no mathematical manipulation necessary -- they just erase the number and write in a new one.

"I don't like to do it," Peter says. "It frustrates me that I need to change that grade."

Coffin says she doesn't see any dishonesty in bumping up a high 40s mark to a 50.

There's a misperception grades are "calculated" rather than "determined," she says. Both Dewar and Coffin say coming up with that final number is an art and a science that's left to each teacher's professional discretion.

Coffin also points out students who get grades of 50 on their transcripts are not likely to continue on to college or university.

At the Ministry of Education, Hunter says the mark-changing policies have been around since 1990 or longer, and until now, he'd never heard questions or complaints about it.

The point, he says, is to give students hovering near the passing line a chance to reach the milestone of graduation. To hand out marks just shy of passing is "inviting controversy," he says.

"It's best to be definitive that way, one way or the other."

When asked whether the policy blurs the line between passing and failing, Hunter insists the passing grade in Saskatchewan is still 50 per cent.

"I just don't see a grey zone that you claim is there."

french@sp.canwest.com

© Copyright (c) The StarPhoenix