Missing bumblebee buzz a concern: Biologists

BY TOM SPEARS, OTTAWA CITIZEN MARCH 9, 2009BE THE FIRST TO POST A COMMENT

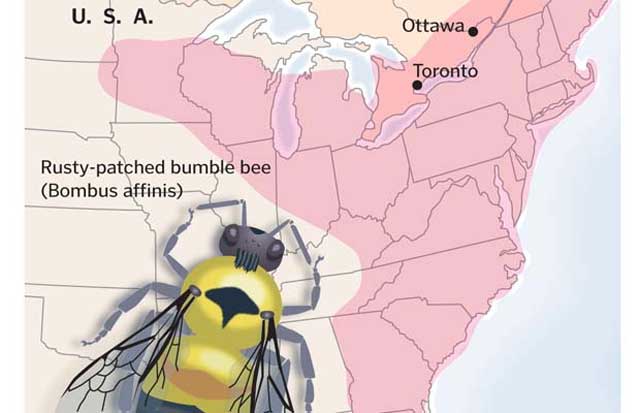

The range of the rusty-patched bumblebee.

Photograph by: Xerxes Society, Ottawa Citizen

OTTAWA — A common bumblebee that buzzed around your home a few years ago hasn't been spotted in Canada in three years. That's bad news if you love insects, or the planet, or if you just love tomatoes.

The rusty-patched bumblebee was one of five or six common bumblebees in the southern half of Ontario.

"It was pretty common in the 70s and 80s, and all of a sudden it's not found anywhere," said Sheila Colla, a PhD candidate in biology at York University.

Colla has searched through 43 sites from Ontario to Georgia to trace the bee's history in eastern North America. These are all places where it used to be common.

Bumblebees pollinate some plants that honey bees do not, including tomatoes, raspberries and sweet peppers. And many bumblebee numbers are declining for unknown reasons.

Why little Bombus affinis — the rusty patched — has buzzed off so completely is a big unknown. But Colla thinks we should take note.

"Bumblebees have this buzz pollination technique where they rapidly vibrate flowers and honey bees can't do that. So when people plant tomatoes in their back yard or cucumbers or sweet peppers, without a bumblebee you will get no fruit. Like, zero. So people are more reliant on them than they realize, because they have this behaviour that is irreplaceable by any other bees."

Her studies find fewer bumblebees overall in Ontario than a couple of decades ago. Half the 14 species found in the 1970s are either missing or in decline.

To the biology student, bumblebees are a rainbow of diversity, shown by stripes. "Some of them are black with one yellow stripe. There's one that is yellow-orange-orange-yellow on the abdomen. And then there's another that's yellow-yellow-orange-orange-orange." All are big and fuzzy.

The rusty patched is named for a single orange blob on its back.

The little bee emerges in April and lives until October, when the queen hibernates and all her subjects die. In its heyday, the rusty patched represented about 15 per cent of all bumblebees someone would see on a summer day.

By 2005, searchers found 9,000 bumblebees in an annual survey, and just one of the 9,000 was a rusty patched. That one was in Pinery Provincial Park, on Lake Huron, and none has been seen in Canada since.

Today it's not extinct, but the closest known specimen seems to be in Illinois, and even there it's incredibly rare.

There are other bumblebees, but they don't all pollinate at the same time of year. If we lose one species, this may leave a gap in the pollination season.

Tomato growers in southwestern Ontario have begun rearing bumblebees indoors to get large numbers of them for pollinating.

"But because they're reared in really artificial conditions, we get the same problems we see in farmed salmon," Colla said. Crowding can breed disease, and she suspects the farmed bees spread disease to wild ones.

"It hasn't been proven that that's the reason for decline," but the decline came shortly after the bee-rearing practice began.

Other possible culprits are habitat loss — though it once adapted well to city gardens — and new pesticides.

Honeybees have been dying because of attacks by mites and other mysterious causes that kill off entire hives in winter; Colla says the bumblebee deaths could be related, but no one really knows.

Her work appears in a research journal, Biodiversity and Conservation.

© Copyright (c) The StarPhoenix